Deaf Culture Values: Sign Language

- by Michelle Jay

- No Comments

American Sign Language is the most highly regarded asset of Deaf Culture. ASL is the natural language of the Deaf, so a strong goal of Deaf advocacy is to preserve ASL.

There are many language systems that have been invented to try to help deaf children learn English—Sign Supported Speech, Signed English, and Cued Speech, to name a few. However, it is believed that using these systems without ASL deprives deaf children of their true language and ability to communicate effectively.

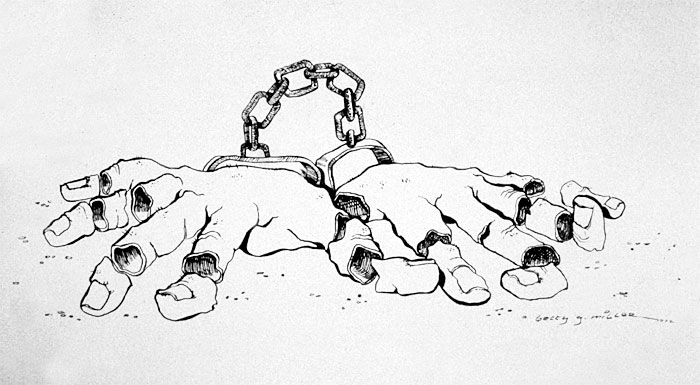

Throughout history, deaf people have been strongly oppressed and even forbidden from using sign language in favor of spoken language.

The artwork above titled “Ameslan Prohibited” was created by Betty G. Miller in 1972. The term “Ameslan” is an early word for ASL that is no longer used. The handcuffs represent how forbidding sign language feels like enslavement to the deaf. And the broken fingers are a violent illustration of the repeated slapping of knuckles with a ruler when deaf children were caught using sign language.

It wasn’t until the 1960’s that William Stokoe, a scholar and hearing professor at Gallaudet University, published a dissertation that proved ASL is a genuine language with a unique syntax and grammar. ASL was henceforth recognized as a national language and this was one of the biggest events in sign language history.

Research shows that if a deaf child is not exposed to sign language in the critical years after birth, there can be permanent harm in brain development.[1] However, still today, oral education and speech therapy is commonly forced on deaf children without the use of sign language.

Sign language is the natural language for deaf children. When speech education is forced, deaf children are deprived of one of their core needs: language. The only language that is truly possible and effective for deaf people is sign language. Spoken English is almost completely useless to the deaf without achieving a strong sign language foundation first. Even if deaf people can learn to read lips, only 20 to 30 percent of the conversation is understood.

Deaf children born to hearing parents

Rachel Kolb, a Stanford graduated and Rhodes scholar, states during her TED talk titled “Navigating Deafness in a Hearing World”:

“I was born profoundly deaf, and learning to speak was not easy. Think about it for a second: when you can’t hear, how do you learn to speak? For me the answer was 18 years of speech therapy.

Society has a tendency to focus on disability rather than ability. And certainly, my abilities are different from many other people’s abilities. I wear a hearing aid in this ear, and a cochlear implant in this one, if I take both of them off, I can’t hear at all. I can’t talk on the phone; I can’t communicate exactly like everyone else.

I use lip reading and sign language instead. But over time I’ve come to perceive myself as far more able than disabled. A large part of this is not taking my challenges as outright limitations.

I was born to hearing parents, who did not know sign language, and who knew almost nothing about deafness when they had me. This is not too uncommon among children who are born deaf.”

Rachel goes on to share some of the following statistics and her analysis:

- About 2 to 3 out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born deaf or hard of hearing.

- 90% of children who are born deaf are born to hearing parents.

- And only 10% of those families ever learn to communicate effectively with their deaf child, by sign language, cued speech, or other means. The other 90% do not.

- Deaf children born to hearing parents are less likely to develop fluent written English than deaf children born to deaf parents.

- On average, deaf children born to deaf parents have a higher level of achievement: they score higher in other academic areas, and demonstrate greater independence and better social skills.

- Only a third of deaf children complete high school.

- Out of the deaf individuals who do attend college, only a fifth complete their studies.

- On the whole, deaf adults earn about a third less than their hearing peers.

- Half of deaf high school graduates read below the fourth grade level and only 7-10% read at the seventh grade level or above. [2]

“These statistics tell a story of a fundamental misunderstanding. I’ll give it to you straight: deaf people are capable of doing anything hearing people can do, except hear. But communicating when you can’t hear exactly like everyone else is not the same as communicating if you are a typically hearing person. Deaf children can face significant challenges in acquiring and using language. These challenges are not insurmountable, by any means. But they’re there, because deafness at its core is a communication barrier. These numbers make me sad. Language is precious to me.” [3]

In her TEDx talk titled “Protecting and Interpreting Deaf Culture,” Glenna Cooper states: [4]

“My parents didn’t know I was deaf until I was 18 months old. My parents’ world fell apart, primarily because of the hearing society’s view on deafness as a negative. My doctor, an ear, nose and throat specialist, told my parents that I should not learn sign language, because it would make me isolated from the hearing community. I had to learn to speak and to read lips to fit in with hearing culture.

So I did. I grew up learning to speak and read lips, trying to fit in with hearing society, and man, it was a challenge. Frustrating. Communication was not always there with a hundred percent access. When I was three years old, I spoke my first word: boat. My parents were driving, and out the window, I saw a boat and kept repeating the word.

My parents, upon looking back, realized that the doctors didn’t really understand the critical part of language development for infants. It’s so critical that deaf babies have a first language, American Sign Language. It’s a natural, visual language for them to develop as a basis, and then they can learn to speak and read lips later in life.

That’s the most important part for deaf babies to have that critical access, that first language. Today, I’m 53 years old. I’m proud to be deaf. American sign language is something that I greatly value because it flung the world wide open for me, even more than I had before.”

Austin Vaday states during his TED talk titled, “Sign Language is my Superpower:” [5]

“I lost most of my hearing at the age of three and gradually became deaf over a span of five years.

A healthy form of communication did not exist with my friends and family. I missed out on the daily conversations, the back-and-forth jokes and the friendships formed out of such bonding episodes. And even though I looked all right on the outside, my internal suffering remained invisible to most.

My language, my learning abilities were hindered compared to those of my peers. I felt lonely. I felt like something was missing. I never felt a human connection. But all of this changed when I started learning American Sign Language at the age of 12.

For the first time in my life I interacted with people like me that relied on the visual rather than on the auditory. Through sign language I was granted equal access to education. I finally felt like I was part of a community. A world that was once black-and-white to me slowly became colorful.”

Lily Weir, a Deaf vlogger shares in her Youtube video [6]:

“My greatest wish is that ASL becomes the first language for all Deaf children. Why? I’m here to share my personal story of growing up in an oral school.

I got a cochlear implant at two years old. It didn’t mean that I could hear and understand everything well. No, I didn’t always understand when hearing people spoke to me because their voices were muffled and difficult to understand. I was the only Deaf student in elementary and middle school. When I hung out with my hearing friends, I usually tried to mimic their facial expressions, mood, and actions in order to fit in with them. Like, if my friends looked happy, I would say, “That’s great!” Or if they looked sad, I would hug them like, “Oh no.” They assumed I could understand them, but I couldn’t. I felt alone.

I felt the same way in class. Like one time, I remembered looking at my teacher and trying to lipread what she was saying to the class. I only got 2 words: “Science pen.” I was puzzled. The class got up and I ended up following them, not understanding what the teacher said. I was completely confused. It was very frustrating. My teacher gave me homework, I told my teacher’s aid that I didn’t understand this, and she told me to just copy the answers. As a result, I didn’t learn anything. I was not learning because I had no access to language.

In the 6th grade, I was placed into a Special Education class and they thought it would be a good fit for me, but it didn’t work out. Why? Because no one signed to me. I continued to struggle. I knew that I could be like other hearing people – independent, knowing how to write and communicate clearly! I wanted the same thing! I was so furious. I knew that something was wrong at school.

I decided that it was time. I followed my instincts. I told my mom I wanted to go to a different school, a Deaf school. I was tired of being the only Deaf student. I felt I was not able to learn as much as I should have. I had my mom’s support. My mom and I visited the DHH program at Venado Middle School in Irvine, California. I was so excited when I arrived because I saw many students just like me – Deaf! Plus, they were signing! I was so amazed at the ease the students had with communicating and understanding. I told my mom, I wanted that!

After, I transferred to Venado Middle School, and learned ASL, and finally felt like I belonged. Communicating became natural. I finally understood my teachers because they were using sign language. I finally understood ideas and concepts that I couldn’t understand before. I did no more copying and started to do my own work.

I realized that I was really behind with my education because I had missed out on so much growing up. I was motivated to catch up, so I communicated with my teachers and asked how I could improve. I worked with tutors, and went to summer school every year, and worked doubly hard.

One year later, because I was not comfortable using my voice and it was not who I am, I decided to stop using my voice. I felt free, comfortable, and happy. It was a personal choice that I made for myself. Of course, I respect my other deaf friends, who wear hearing aids, cochlear implants, and use their voice. If they’re comfortable and happy, that is great!

I can’t imagine not having ASL. I would have continued to struggle and fail. I’m very proud to be Deaf. I cherish my culture, my language, and my community – it’s all a part of my identity. Now, I’m a senior and will graduate soon from University High School. And this coming fall, I’ll be going to Gallaudet University. ASL saved my life!”

As you can see from the statistics shared by Rachel Kolb and the personal stories shared by Rachel, Glenna Cooper, Austin Vaday, and Lily Weir, these are common experiences held by deaf children. Most do not learn sign language during their formative years and this greatly affects their education and development into adulthood. As the speakers above have expressed, learning sign language changed their lives for the better. And while a few deaf children do successfully learn how to use spoken English – we must ask ourselves: at what cost?

Deaf children born to deaf parents

The experiences of deaf children born to hearing parents can be contrasted with the experiences of the few deaf children born to deaf parents.

In his TEDx talk titled “Why we need to make education more accessible to the deaf,” Nyles DiMarco shares: [7]

“Many of you may not know that I come from a rather large family. I have two brothers who are also Deaf along with my parents, my grandparents, and yes, even my great-grandparents as well. I’m the fourth generation in a beautiful family with over 25 Deaf members.

Born to Deaf parents who understood the Deaf experience, they knew exactly how to raise me. They knew how to provide me with the best opportunities and to support me. From day one of my existence, my parents gave me language, access to education, and love. Growing up, my life was perfect. Imagine, like many of you born to hearing parents, I never noticed barriers that simply weren’t there. I’m sure many of you felt your life was normal, the same way that I did. Coming from a Deaf family, my world, in every way, was a utopia.

When it came time for my parents to enroll me in school, they already knew that I would go to the Deaf school. I would learn in an environment that was designed for me. At that time, all of my peers, and teachers, and even the superintendent was Deaf. So, I was still in my perfect world. I was in an environment where I could grow and where I could thrive. And I had no problems; it was perfect for me. And many people don’t believe that, but it’s true. For me, the Deaf community, our world, was the perfect world for me.

And I remember in the summer before fifth grade, I was ready to go back to school, and I asked my mom to go to a public school. She thought I was crazy. She said, “What?! No! Public school, it’s all hearing kids. The Deaf school is a perfect fit.” And I said, “No, I want to learn what those students are learning. I want to see what their classrooms are like. What are public school teachers like?”

So upon my insistence she enrolled me. And after two weeks of frustration, I came home pleading to go back to the Deaf school. She listened very sympathetically and told me, “Nope, too bad.” I was floored. She told me I needed to stick it out for a year because I needed to learn how to interact with my hearing peers, and that if I gave it a little patience, I would learn so much about the world around me. Because the reality is the world is hearing.

I was the only Deaf kid in the entire school. Of course, I always had hearing friends, but they could sign like me. So that year I gained a lot of insight. I couldn’t be involved in any of the school organizations. My friends never learned enough sign to communicate. And every time I tried to play a sport, I’d get benched. The basketball coach told me a Deaf kid could never help the team win a game. And I was athletic.

So after a year, I went back to the Deaf school where I realized that’s my home. That’s my community. And my community is where I can thrive. I got involved in the classroom again, joined a bunch of school organizations, and got back on the basketball team, where I helped win many games. So it’s without hesitation that I can say the Deaf community is in fact my home.

There are currently more than 70 million deaf people in the world with only two percent of them having access to education in sign languages. Which means millions upon millions of deaf children not receiving the education they need, also known as education deprivation. I also learned that over 75 percent of hearing parents don’t sign to communicate with their deaf children. Which is astonishing. Again, imagine millions and millions of deaf children without an education, without a language. Those children without language and access to education exhibit signs of brain damage. In my research, I also found that I’m a part of an even smaller group. Ten percent of Deaf children come from Deaf parents like mine. Only 10 percent. I’m incredibly lucky. I had access to language, an education, and I had parents who loved me and put me on a path to success. I wouldn’t be who I am today without any of those things.”

Learning sign language is such an important developmental milestone for the deaf. Too many deaf children are left struggling with learning speech when sign language – their natural language – is available to give them the language and communication abilities that they need to grow and thrive.

Research conducted by VL2’s 15 national and international laboratories and the Petitto Brain and Language Laboratory for Neuroimaging at Gallaudet [8] shows that:

- Speech is not privileged in the human brain, but is biologically equivalent to sign language. ASL is processed in the same areas of the brain as spoken English; these key brain areas are not specialized exclusively for sound, but are specialized in processing the patterns on which language is built.

- Early exposure to visual language confers significant visual processing advantages and maintains the infant brain’s sensitivity to the language patterns it must experience within the required developmental timeframes.

- This exposure does not harm young deaf children or delay spoken language development, but keeps their brains’ language tissue and systems ‘alive’ and propels the acquisition of spoken English.

- Early exposure to ASL supports strong English speech skills and better vocabulary and reading skills compared to hearing peers learning only English.

- These deaf children have the identical benefits found in children who are bilingual in other languages, including more robust use of the language areas of the brain, enhanced social and interpersonal understanding, and stronger language analysis, reading, and reasoning skills.

- Parents of young deaf children who are learning sign language do not need to achieve immediate and full fluency during this timeframe for their children to benefit from early exposure to ASL.

- Studies show young deaf children exposed to signed languages achieve every milestone on the exact same timetable as young hearing children exposed to spoken languages. The signed and spoken language timing “windows” are identical.

And still, despite these findings, the oral/speech education model for deaf children is still used widely today.

For this reason, the Deaf very strongly advocate for the protection and basic human right of access to sign language for deaf children. They strongly support the Bilingual/Bicultural education method where deaf children learn sign language first as a foundation and then learn to read and write English. As Rachel Kolb states, “Deaf children born to hearing parents are less likely to develop fluent written English than deaf children born to deaf parents.”

The World Federation of the Deaf has argued that, “being allowed to develop their cultural and linguistic identities – including in educational settings – is a key right of deaf children. And that methods of education which best promote the development of such identities are full sign language/bicultural models of education where education is delivered in national sign language (not just interpreted into sign language which has been suggested as a reasonable accommodation) in an environment where all people can/are competent in and use sign language. This is a strong form of what multilingualism research calls a mother-tongue-based multilingual education (where the “multilingualism” in the case of deaf children means reading and writing in another language or languages). Denial of the right to learn and use sign language (including from birth) in any environment is arguably a breach of Article 27 of the ICCPR and/or (where it relates to children) of Article 30 of the CRC.” [9]

Many Deaf people believe deaf children should be educated at Deaf schools where deaf students are able to learn in their natural language and are taught by Deaf teachers who can become strong role models. Deaf children can join sports teams, make lifelong friends, and be a part of a community where they are the same as everyone else.

When deaf children are a part of mainstreaming programs, they attend regular classes and special education classes at a public school. Mainstreaming is supposed to allow deaf children access to regular education. However, mainstreaming does not offer the best social interaction for deaf students. Communication between teacher and student is always through an interpreter in regular classrooms. Students can miss out on group discussions as well as sounds and interactions that occur outside the classroom.

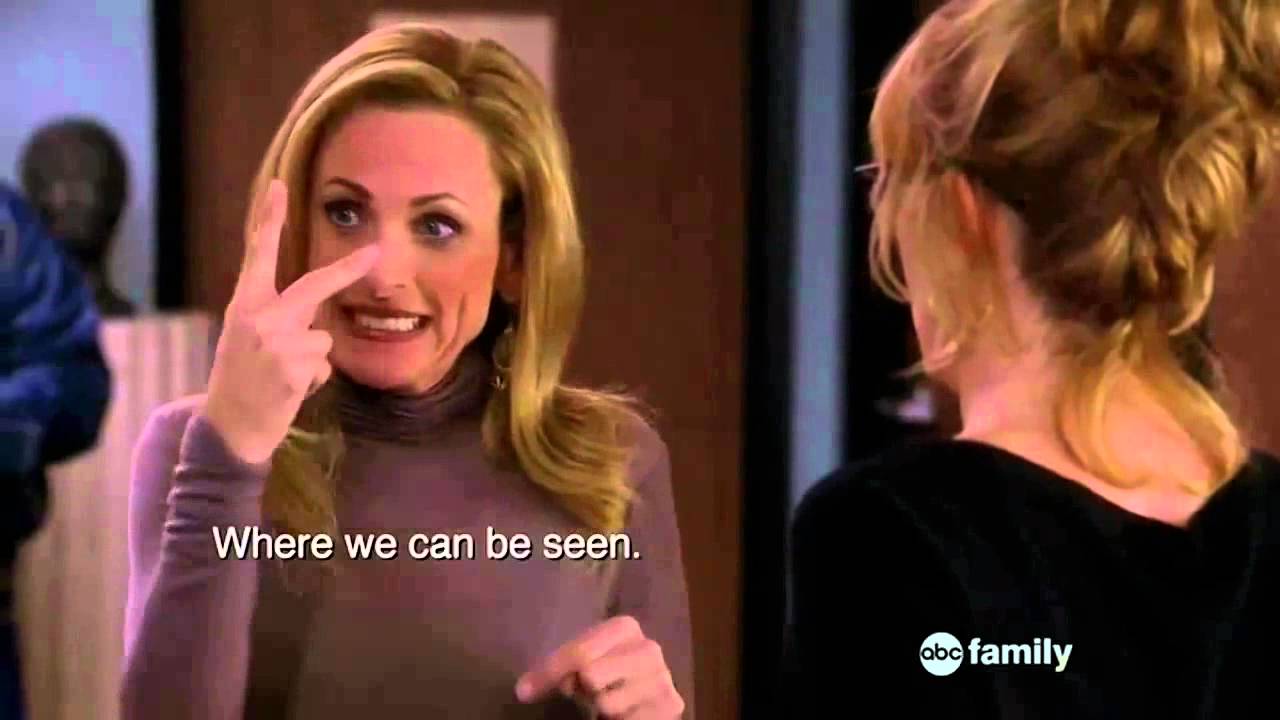

In a scene in the ABC Family television show Switched at Birth, the differences between these two types of education options is illustrated very well. In one scene, Melody (played by Marlee Matlin), has a confrontation with Kathryn (played by Lea Thompson) regarding the hearing program that was added to the deaf school.

Melody explains why the Deaf so strongly fight to protect the positive Deaf community experiences of deaf children:

Kathryn: I think we are building something great here. Hearing and deaf kids working together. I don’t understand why you don’t think we can co-exist.

Melody: This is a deaf school. Where we can be seen. But the world doesn’t recognize us.

Kathryn: That’s not true of all hearing people. I recognize you.

Melody: And that’s nice. But you’re here because you’re a parent.

Kathryn: Actually, I’m here because you can’t afford a drama teacher. And the hearing program will help you by bringing in more money. What’s so bad about more money for the school?

Melody: Because of what it will cost us! At a hearing school, deaf students will always be on the outside. They enter the cafeteria for lunch, they look around, see twenty different conversations, none of which they can be a part of. Here they’re free. Not to be the “deaf kid”, but to be themselves. And that’s what I’m fighting for. And if you can’t see why that’s more important than your play or anything else, then I don’t know what else to tell you! [10]

For all of these reasons, the Deaf advocate that deaf children have the right to education in their natural language and within their own community where they can fully learn, develop, and truly thrive.

When we discuss sign language as a core value of Deaf culture, it is because it is treasured by the Deaf from birth. Sign language is how the Deaf communicate and experience the world. And the ones who had been deprived of their natural language for too long are fighting to make sure the deaf children of the future do not encounter the same struggles they did.

Resources:

[1] “Announcements: VL2 Provides References for President Cordano’s Statement.” Gallaudet University. 11 April 2016. https://vl2.gallaudet.edu/news/announcements/references-president-cordanos-statement. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[2] Hrastinksi, Iva and Ronnie B. Wilbur. “Academic Achievement of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students in an ASL/English Bilingual Program.” The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, Volume 21, Issue 2. April 2016. https://watermark.silverchair.com/env072.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[3] Kolb, Rachel. “Navigating deafness in a hearing world.” TEDxStanford. 20 June 2013. https://youtu.be/uKKpjvPd6Xo. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[4] Cooper, Glenna. “Protecting and Interpreting Deaf Culture.” TEDxTulsaCC. 22 May 2017. https://youtu.be/io7z5PftOU4. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[5] Vaday, Austin. “Sign language is my superpower.” TEDxUCLA. 22 June 2018. https://youtu.be/Jkp8syLbDs8. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[6] Weir, Lily. “I’m Proud to be Deaf!” Ai-Media. 3 April 2017. https://youtu.be/Jkp8syLbDs8. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[7] DiMarco, Nyles. “Making Education Accessible to Deaf Children.” TEDxKlagenfurt. 5 September 2018. https://youtu.be/U_Q7axl4oXY. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[8] “Announcements: VL2 Provides References for President Cordano’s Statement.” Gallaudet University. 11 April 2016. https://vl2.gallaudet.edu/news/announcements/references-president-cordanos-statement. Accessed 6 July 2020.

[9] Down, Elena and Dr. Robert Adam. “WFD Position Paper – Deaf Community as linguistic identity or disability.” World Federation of the Deaf. March 2017. https://wfdeaf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/LM-and-D-Discussion-Paper-FINAL-11-May-2018.pdf Accessed 6 July 2020.

[10] “Switched at Birth ‘And that’s what I’m fighting for!’” Switched at Birth | ABC Family. Posted 4 April 2015. https://youtu.be/EtyN_Apof0Y. Accessed 6 July 2020.